Japan, a nation often seen as a trendsetter in technology but slower in social shifts, is now grappling with challenges that have defined Western politics for years: the rise of nativist populism. This shift is exemplified by the emergence of new political parties like Sanseito, whose platform echoes “Japanese First” sentiments, driven by growing concerns over immigration and the pervasive impact of overtourism. This article examines the factors behind these developments, their current implications, and potential paths forward for Japan.

Contents

The Emergence of Nativist Populism in Japan

For an extended period, mainstream Japanese politics largely avoided the xenophobic and nativist populism seen in movements like MAGA in the United States or parties such as AfD in Europe. Former Prime Minister Abe Shinzo, who governed from 2012 to 2020, was considered a rightist but often acted as a conservative, even liberal, leader. He notably opened Japan to immigration and championed women in the workplace. When an anti-Korean hate group emerged in the early 2010s, Abe’s government enacted Japan’s first law against hate speech and placed the group on a watchlist, effectively neutralizing its political influence.

However, recent trends indicate a change. A new political party, Sanseito (often translated as “Political Participation Party”), has secured a notable number of seats in Japan’s Upper House election. Founded in 2020 by former supermarket manager Sohei Kamiya, the party gained traction online and during the COVID-19 pandemic, spreading conspiracy theories about vaccinations and global elites. Its “Japanese First” campaign resonates with frustrations over stagnant wages, high inflation, rising living costs, overtourism, and the influx of foreign residents. Sanseito advocates for caps on foreign residents, stricter immigration policies, and reduced benefits for non-citizens, alongside calls for stronger security, tax cuts, renewable energy, and a health system less reliant on vaccines. While some of its rhetoric, like anti-vax sentiment and references to “globalist elites,” mirrors Western populist narratives, the primary focus on immigration and tourism reflects specific domestic concerns.

Drivers of Global Migration and Japan’s Response

The global increase in migration stems from several interconnected factors. First, the internet provides people in developing countries with unprecedented information about life and opportunities in wealthier nations, encouraging movement. Second, as countries escape poverty, their citizens gain the financial means to emigrate. Third, declining fertility rates in developed countries, including Japan, lead to long-term population shrinkage and labor shortages across various industries. To address these economic and social disruptions, most rich nations eventually turn to immigration. Japan, though initially slower to adopt this strategy, has increasingly followed suit.

For a detailed account of Japan’s decision to embrace immigration, interested readers can explore why Japan opened itself up to immigration. The general trend shows that Japan has, in fact, opened its borders.

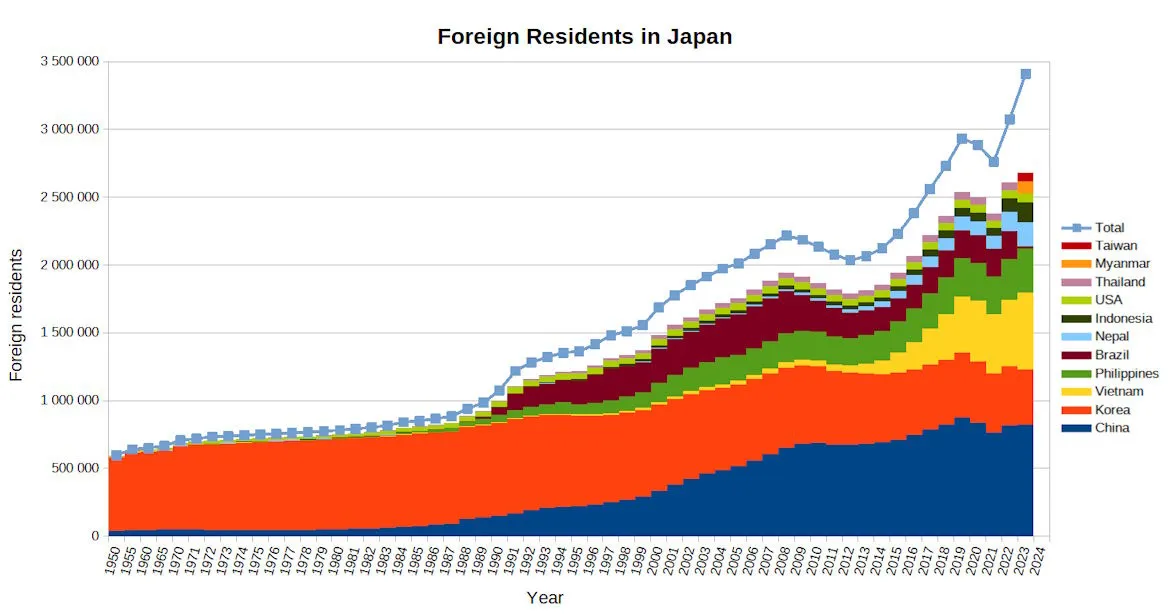

Graph illustrating the increasing number of foreign residents in Japan by nationality from 1950 to 2020, highlighting trends in immigration.

Graph illustrating the increasing number of foreign residents in Japan by nationality from 1950 to 2020, highlighting trends in immigration.

While a significant “Korean” population on historical charts primarily refers to “zainichi” individuals whose ancestors immigrated from Korea and are functionally Japanese, the substantial influx of foreign residents only truly began in the 1990s, with “true permanent mass immigration” starting around 2013. This recent wave primarily includes people from Vietnam, the Philippines, and Nepal, though other Southeast Asian countries, as well as the U.S. and Taiwan, are contributing to the evolving demographics. This immigration is visibly noticeable in daily life, with a growing number of foreign clerks in convenience stores and cooks in restaurants. Furthermore, the diversification of Japan’s youth population is occurring even more rapidly than the overall population, as these numbers only account for the foreign-born, not their children.

Potential Societal Impacts of Increased Immigration

The long-term effects of large-scale immigration on Japan’s distinct characteristics are an open question. Japan is not a traditional “nation of immigrants” like the United States; its national identity has historically been rooted in a unique culture not immediately shared by newcomers. While mass immigration has not yet drastically altered the overall character of major cities like Tokyo and Osaka, specific areas are experiencing significant changes.

For example, Japan’s Muslim population now exceeds 200,000, leading to the establishment of mosques, Muslim schools, and Muslim graveyards, which are reshaping some neighborhoods. Traditional Japanese graveyards are compact due to cremation, but the Muslim religious practice of burial requires more land, presenting a unique challenge in a land-constrained country.

Concerns also extend to public safety. Japan is renowned for its extremely low violent crime rates, which allow women and children to walk safely at night—a freedom unfamiliar to many in other developed nations. This high level of public safety also enables the development of dense, walkable cities. Immigrants in Japan generally exhibit surprisingly law-abiding behavior. While official statistics suggest foreigners are arrested at a slightly higher rate (less than twice) than native-born Japanese, the baseline crime rate in Japan is so low that even this increase has a minimal impact on the national character. For instance, Japan’s murder rate is approximately 0.23 per 100,000 people; doubling that would still place it safer than countries like South Korea or China. However, if the foreign-born population continues to grow significantly, especially reaching levels seen in countries like the UK (16%), there is a concern that large enclaves of foreign residents could form, potentially leading to a breakdown in acculturation to low crime rates, similar to experiences in certain European cities.

It is therefore understandable for some Japanese citizens to feel uneasy about continued mass immigration, reflecting a genuine apprehension about potential long-term changes to societal norms.

The Overtourism Phenomenon

Beyond immigration, another significant factor fueling nativist sentiment in Japan is the issue of overtourism. Thanks to a decades-long concerted campaign by the national government, Japan has become globally recognized as an incredibly unique, pleasant, and accessible travel destination. Modern technology, including translation apps, Google Maps, cheap international roaming, and mobile payment systems, has made visiting even easier. The recent weakening of the Japanese yen has also made the country a more affordable destination for international travelers, leading travel experts worldwide to consistently recommend Japan.

As a result, Japan has experienced an unprecedented influx of tourists. In 2024, the country is projected to host approximately 37 million international travelers.

Bar chart displaying the rapid growth of international visitors to Japan from 2005 to 2024, showing the significant increase in tourism.

Bar chart displaying the rapid growth of international visitors to Japan from 2005 to 2024, showing the significant increase in tourism.

While 37 million annual visitors might seem small relative to Japan’s total population if dispersed evenly, tourists are not distributed uniformly across time and space. They often crowd into specific areas—such as west Tokyo or Kyoto’s historic districts—during peak seasons like the cherry blossom period. During these times, areas like west Tokyo can feel as densely international as major global cities, with coffee shops, restaurants, and parks overflowing with foreign visitors, many of whom do not speak Japanese. Train stations become congested, and securing dinner reservations can be nearly impossible.

In some neighborhoods, the congestion subsides during off-peak seasons, but many of Japan’s most beautiful and vibrant spots have been transformed into tourist-centric areas. Golden Gai, once a hub of unique local bars in Tokyo, is now predominantly populated by tourists. Shibuya, historically a center of Japanese youth culture, has become a self-referential museum, and Akihabara, known for its subculture, now caters mainly to tourists seeking generic stores. Kyoto, in particular, has seen its distinctive character overshadowed by a constant throng of visitors, with some areas becoming overly commercialized to serve foreign demand.

This phenomenon is often described as a “congestion externality,” where the collective impact of many individuals degrades an experience that would be enjoyable for a few. Such externalities also strain Japan’s highly efficient public transit systems and meticulously designed streets. Cities are optimized for continuous occupancy, but tourism is seasonal. Building infrastructure to handle peak tourist loads means underutilization during off-seasons, while optimizing for average ridership leads to overwhelming congestion during peak times, creating an unsatisfactory situation.

Tourist behavior also contributes to local frustrations. Unlike immigrants, who often acculturate over time, tourists typically spend less time in a country and may not fully grasp local rules and norms. This can result in disruptive behavior, as evidenced by numerous online videos and high-profile incidents involving streamers engaging in inappropriate conduct to gain online attention.

Placeholder image for a YouTube video showing tourists behaving disruptively in Japan, illustrating overtourism issues.

Placeholder image for a YouTube video showing tourists behaving disruptively in Japan, illustrating overtourism issues.

Placeholder image for a YouTube video capturing instances of unruly tourist conduct in popular Japanese locations.

Placeholder image for a YouTube video capturing instances of unruly tourist conduct in popular Japanese locations.

Placeholder image for a YouTube video depicting various examples of tourists failing to adhere to local norms in Japan.

Placeholder image for a YouTube video depicting various examples of tourists failing to adhere to local norms in Japan.

While these actions are not criminal in the same vein as violent crime, they undeniably impact the character of a nation like Japan. The anti-foreigner sentiment fueling Sanseito’s rise is thus not solely due to immigration but also significantly influenced by the challenges posed by overtourism. The central question for Japan is when this trend will end. Without proactive measures, there is a risk that Japan’s major cities could permanently become theme parks, similar to places like Venice. Implementing policies such as a surcharge on hotel reservations made via foreign bank accounts in popular destinations could help redirect international travelers to less-visited cities and rural areas, while also generating revenue. Additionally, stricter enforcement and punishment for criminally disruptive tourist behavior, mirroring Singapore’s approach, could help maintain public order and respect for local norms.

Addressing Challenges: Selectivity and Assimilation

Despite the rising nativist sentiment, anger at immigration has not yet become the dominant national mood in Japan. Recent polls indicate that pro-immigration sentiment has, in fact, increased in recent years.

Poll results showing Japanese public sentiment towards immigration in 2024, indicating an increase in favorable opinions.

Poll results showing Japanese public sentiment towards immigration in 2024, indicating an increase in favorable opinions.

However, as seen with movements like MAGA in the U.S., a dedicated and vocal minority can generate significant national disruption. Japan’s ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), traditionally known for its ideological flexibility and responsiveness to voter concerns, will likely need to address these issues to prevent the further rise of populist figures.

Improving Immigrant Selectivity

One key area for action is improving immigrant selectivity. Japan has faced challenges in attracting large numbers of skilled immigrants, partly due to lower entry-level salaries and the language barrier. However, as some Western countries become less appealing destinations, Japan could emerge as an attractive alternative. Intensified efforts to recruit skilled professionals are crucial. Beyond skills, Japan could strategically target immigrants from countries with cultural and religious similarities, such as Vietnam and Thailand. Additionally, attracting political dissidents from China or refugees from the Hong Kong crackdown could be a viable strategy.

Enhancing Assimilation Policies

Another vital step is to enhance assimilation policies. Japan’s existing system for immigrants was largely built on the premise that they would be temporary residents or guest workers who would eventually return home. This approach has sometimes led to foreign children attending separate schools, potentially limiting their Japanese language proficiency and acculturation. It is important for children born to foreign residents in Japan to attend Japanese schools to ensure language acquisition and, more crucially, to facilitate their integration into Japanese societal norms. International schools should ideally be reserved for children whose parents intend to leave the country in the near future.

Consideration should also be given to residential dispersal policies aimed at preventing the formation of ethnic enclaves that might resist integration into Japanese culture. While Singapore actively enforces racial diversity within apartment blocks, Japan may not pursue such stringent measures. However, the government could explore incentives like vouchers for foreigners to reside in areas where their population is currently sparse, thereby encouraging broader distribution and faster assimilation. Breaking up poor immigrant enclaves, as Denmark has done, is another model worth examining.

Furthermore, providing free, intensive Japanese language classes for all immigrants intending to settle in Japan could significantly aid assimilation. These classes could also serve as networking events, inviting Japanese speakers and conversation partners to foster connections. Such initiatives could be tailored to specific industries, allowing Japanese engineers, for example, to meet immigrant engineers, thereby embedding newcomers more quickly into Japanese society.

Unless Japan chooses to reverse its course on immigration, which could have negative economic consequences, it will need to develop effective strategies to assimilate new residents. Observing the evolving assimilation policies in European countries, while not necessarily copying them directly, can offer valuable lessons.

Conclusion

The rise of nativist politics in Japan, exemplified by the Sanseito party, reflects growing domestic anxieties tied to increased immigration and the pervasive challenges of overtourism. While Japanese public sentiment towards immigration remains largely favorable, the concerns of a vocal minority underscore the need for proactive policy responses. To address these issues and ensure long-term societal stability, Japan’s leaders are challenged to improve immigrant selectivity, focusing on attracting skilled individuals and those from culturally aligned nations. Simultaneously, robust assimilation policies, including comprehensive language education and measures promoting residential dispersal, are essential to integrate newcomers effectively and preserve Japan’s distinctive social fabric. By demonstrating their traditional adaptability, Japan’s leaders can navigate these evolving complexities and mitigate the rise of divisive political movements, securing a harmonious future for all residents. For further insights into Japan’s demographic shifts and policy responses, explore related analyses on migration trends and cultural integration.